Warning: Trigger Warnings

How Trigger Warnings Change our Relationship to Potentially Distressing Material: Reactions, Anticipation, Avoidance, and Learning

This is Part 4 of a five-part series on why distress is not damaging.

I think I encountered my first trigger warning circa 2016, and I can’t say I thought much of it other than that it seemed to be a solution in search of a problem. The innocuous little warning alerts you to the potentially distressing nature of content you’re about to encounter, content you might not have found particularly distressing, but now you’re wondering…

The underlying assumption behind trigger warnings is that people who have had negative experiences may feel distressed when encountering content that reminds them of these negative experiences – i.e., the content triggers negative emotions relevant to prior negative experience. The purported purpose of these warnings is to help the people they’re aimed at emotionally prepare for the content they are about to encounter or avoid it entirely if they prefer.

It seems we’ve been missing a trick in the world of trauma therapy if we haven’t been applying these warnings all this time. It never came up in training, which seems like an oversight if it’s something we should have been doing. I mean, in trauma therapy we talk about some pretty gnarly stuff, so if anyone ever needed a warning, it was our clients. Oops.

Trauma, triggers, and avoidance

As a trauma therapist I’m very familiar with the notion of triggers. Triggers are sensory stimuli that can cause people with PTSD to re-experience the traumatic events that gave rise to their distress. This re-experiencing can take place in the form of intrusive thoughts or images, nightmares, or flashbacks. We’ve probably all experienced intrusive thoughts or images, especially when we’re going through a stressful phase, and we’ve all had at least a handful of nightmares in our lifetime. But I’m not talking run-of-the-mill stuff; I’m talking chronic, highly disruptive, and potentially debilitating. Flashbacks are seriously gnarly departures from reality where the individual loses contact with the present moment and literally feels as though they are re-living the event. Sounds like something you’d want to avoid, right? So, it’s only natural that people with PTSD tend to avoid sensory triggers – usually sounds, smells, places, or contexts that are reminiscent of the traumatic experience.

But therapy for PTSD involves breaking that avoidance cycle and exposing the individual to titrated doses of thoughts, feelings, memories, or situations they instinctively want to avoid. That means leaning into triggers, and learning to cope with the distress they generate. By flexing some coping muscle and allowing this exposure, the brain comes to fixate less and less on the distressing content, and the traumatic experience becomes integrated into the broader fabric of the individual’s life story. No longer a central aspect of their life, the trauma ceases to dominate their every move. But when folks fear that they can’t cope with distress, avoidance comes to govern their life, and, in extreme cases, they may become unable to work, socialise, or even leave the house.

So, the idea that trigger warnings could protect people always seemed somewhat absurd to me, because you can’t protect people from 100% of potential triggers 100% of the time. And even if you could, that would mean treating the traumatic event as central to the individual’s life, dominating their every move, demanding coddling from the outside world, and never moving toward recovery.

Sure, a combat veteran can avoid watching a movie that depicts scenes that hit too close to home. But who’s thinking of them on New Year’s Eve, when the sound of fireworks could send their amygdala back to the battlefield where they lost beloved brothers in arms? And who’s thinking of the firefighter at a backyard barbecue, where the smell of overdone steak smoking on the grill could bring back the screams of a child trapped in a burning apartment block, just out of reach? And who’s thinking of the sexual assault victim who feels their attacker’s hot breath on their neck every time their colleague who wears a certain cologne walks past their desk?

The triggers that are hardest to avoid are precisely the ones that send people places their mind is most afraid of. So, how could a basic warning about written, spoken, or visual content provide an adequate blanket of protection that might render therapy redundant? I’m all for being done out of a job on the basis that no one needs therapy anymore, but I’m more than skeptical that trigger warnings are coming for my job.

Cherries to pick

But what if trigger warnings aren’t really for people with PTSD? What if they’re helpful for folks with garden-variety anxiety who aren’t triggered by sensory stimuli, but are instead triggered by their own worries about things popping up that they’re not prepared to cope with? Perhaps issuing a warning of impending distress could help them prepare better, and thus manage their anxiety? I’m doubtful.

Just intuitively, I’ve long suspected a trigger warning might spark anticipatory anxiety out of proportion to the actual content, and that might lead people to become more distressed than the situation warrants. And if that leads to avoidance, that’s probably not a good thing, what with avoidance being the key maintaining factor in anxiety. But that only goes for people who lean anxious. For those who don’t, I’ve assumed the warning would read the same as the old parental advisory stickers some do-gooders stuck on all the good CDs when I was a teenager: something interesting here, lean in.

Over the last few years, the evidence has started racking up, so there are some answers to my questions. But the findings are somewhat mixed, and we all know what people do with mixed results: they pick the cherries that support their sociopolitical standpoints. I’m no less likely to cherry-pick than anyone else if I’m honest with myself. So, I have to make an academic exercise out of chasing this rabbit if I’m to avoid getting stuck down a hole I might later need to dig myself out of.

The real pioneering research on trigger warnings comes out of Harvard University, where Ben Bellet and his team found that participants provided with a trigger warning prior to reading a distressing passage of literature turned out to be no more or less anxious than those who were not provided with a trigger warning. This suggests trigger warnings had no effect on content-related anxiety.¹ The media latched onto these findings and reported them variously, some even saying the study proved trigger warnings were helpful for university students, and others saying exactly the opposite, that trigger warnings are harmful. The study didn’t actually sample uni students. Bellet and his team got the hint, and replicated their study, this time in a sample of students. And this time their findings were different: the students who received trigger warnings felt slightly more anxious than those who did not.²

Are uni students just different? Perhaps more prone to anxiety? Or more likely to interpret the warning as a reason to become anxious? We don’t actually know, though my own anecdotal experience of young people on the contemporary campus now dominated by Gen Z is that there does seem to be more anxiety in the air than there was when I was an undergrad. That, and a much stronger collective belief that potentially distressing material will cause distress, and that that distress is not tolerable. But anecdata is not empirical evidence.

Building on the confusion of Bellet’s studies, Mevagh Sanson and team at the University of Waitako in New Zealand found a small decrease in negative emotions after trigger warnings in an online crowdsourced sample, while Guy Boysen’s team at McKendree University in Illinois found no effect in a similarly designed study.³ ⁴ Ho-hum.

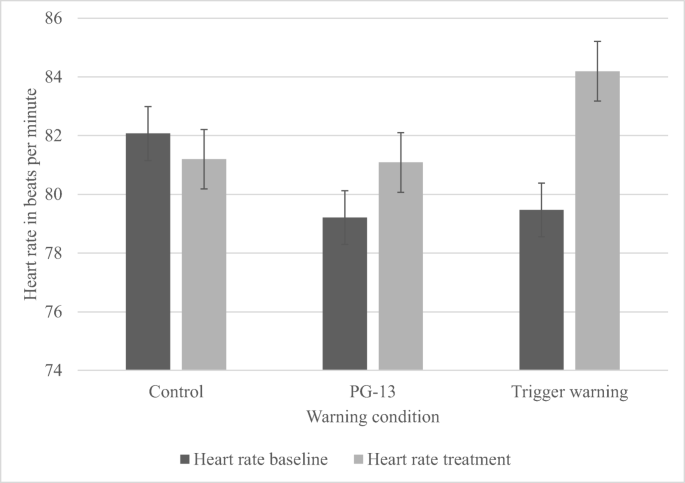

Madeline Bruce and her team at Knox College, Illinois, went a step further with their study. Instead of asking participants to self-report their levels of anxiety (most studies rely on self-report, which relies on participants being both self-aware and honest, so is inherently limited but not fatally flawed), they applied psychophysiological measures to get a more accurate read.⁵ They measured participants’ heart rate, respiration rate, and skin conductance – all validated measures of stress and anxiety – and found that participants provided with trigger warnings exhibited more physiological signs of anxiety than those who did not receive trigger warnings.

More recently, Payton Jones’s team at Harvard explored the effects of trigger warnings specifically in the population they were originally intended to help: trauma survivors. And they found no effect of trigger warnings on anxiety.⁶ That means trigger warnings were of no help to the people they were designed to help. Not in this one study, anyway.

How to make sense of the mixed findings?

Well, the cherry-picking has to stop. We need to look at the entire body of evidence gathered to date, not just studies that affirm our biases. A meta-analysis published just last year is probably the best place to start, as it aggregates all relevant empirical data collected on the topic to date, and weighs it all up.

Getting meta

Victoria Bridgland, based at Flinders Uni in South Australia, teamed up with Payton Jones and Ben Bellet to sift through the literature on trigger warnings to date. What they found was not great quality for the most part – mostly theoretical papers that postulate but do not test hypotheses. Their sifting narrowed down the pool to just 12 empirical studies that met selection criteria: random assignment of participants to experimental and control conditions, and empirical testing for one of four main outcomes. They then meta-analysed the data, seeking to understand how trigger warnings impact: 1) emotional reactions to material, 2) anticipatory emotions, 3) avoidance, and 4) comprehension of content.⁷

They found that trigger warnings overall had literally no effect on emotional responses to potentially distressing material – i.e., they did not protect people from distress, but neither did they generate content-related distress. And this was the case irrespective of how studies were designed or whether participants had trauma histories. That said, in samples where participants had clinically relevant levels of PTSD, trigger warnings were associated with more anxiety. Yes, you read that right: trigger warnings made people with PTSD more anxious, not less. Maybe we trauma therapists do know what we’re on about after all: when we presume poor coping instead of trying to boost coping, traumatised people don’t do well.

My hunch about anticipatory anxiety was borne out: trigger warnings did elevate anticipatory anxiety. That means they made people worried that the upcoming content would cause them distress. In essence, they were triggered by the trigger warning. And this finding was more pronounced in the studies that used the arguably more objective psychophysiological measures of anxiety. Again, trauma history had no bearing on outcomes.

My concern that this anticipatory anxiety might generate avoidance was not entirely upheld by the findings, though. As it turns out, the findings were mixed. Studies that split participants into groups that either received trigger warnings or did not found no effect of trigger warnings on whether participants avoided or engaged with the material. But the studies that exposed all participants to both content with and without trigger warnings found a morbid curiosity effect – i.e., participants consistently chose to engage more with the content that had the trigger warnings attached. Well, that is not what the warnings were intended to achieve, though it does align with my suspicion that folks’ curiosity gets piqued by warnings, just like how those parental advisory stickers lent greater appeal to music considered damaging to 90’s teens.

And on the last point, the last bastion of Team Trigger Warning: did trigger warnings help or hinder comprehension of the content they were applied to? (Is it just me, or does it seem a little unrealistic to hope for improved comprehension if the warning leads to outright avoidance of the content?) This one turned out to be a nothingburger: trigger warnings neither helped nor hindered comprehension, so cannot be either recommended or cautioned against for educational purposes.

So, the Bridgland-Jones-Bellet meta-analysis seems to demonstrate that trigger warnings are not doing what they are intended for: helping people prepare for and/or avoid potentially distressing content. What they actually do is raise anticipatory anxiety, and yet somehow generate sufficient morbid curiosity that people lean in. Thankfully that doesn’t seem to result in content-related distress, though. Just distress generated by the warning.

<Eye roll.>

Where to from here?

Trigger warnings turn out to mostly be a nothingburger, neither helpful nor harmful in most cases. So, perhaps it doesn’t matter whether people use them or not?

Well, I would argue that trigger warnings trend toward a net negative when we consider that the warnings themselves are actually triggering, and that if you have PTSD they can actually be somewhat harmful. And trauma survivors are, after all, the population the warnings were originally designed to protect. Some of Ben Bellet’s most recent (yet to be published) longitudinal research also indicates that repeated exposure to trigger warnings is associated with lower coping efficacy over time – i.e., when people keep receiving trigger warnings, they come to believe they cannot cope with potentially distressing material. That’s precisely the opposite of what we’re trying to achieve in trauma clients, as improved coping efficacy is the pathway to recovery.

So, what do we do now that we know this? Well, in my experience, most folks at uni will continue applying trigger warnings to all content that could cause the slightest flicker of discomfort or potential offence. The enthusiasm has, for a while now, been ahead of the evidence on this, and that enthusiasm is hard to tame. Especially when egos get invested in viewpoints. It’s hard for academics to backpedal when it means admitting their actions were not evidence-based, and perhaps even more so when it might leave students feeling that suddenly no one cares whether they get ‘triggered’. We are, after all, investing a lot of resources in coddling this particular generation of undergrads, to their ultimate detriment.

But outside of that context, wherever you have any sway, I’d be issuing a (metaphorical) cease-and-desist notice. If we want to protect people from distress, then trigger warnings aren’t the way to do that, as they make some people anxious and potentially avoidant of experiences they could otherwise learn and grow from, and they may reduce trust in our own coping skills. If we’re pragmatic, we won’t sacrifice opportunities for learning and growth at the dubious altar of coddling. As we well know by now, distress is not damaging, but a perceived inability to cope leads us to shrink out lives to fit our fears. And that, my friend, is damaging.

References

Bellet, B.W., Jones, P.J., & McNally, R.J. (2018). Trigger warning: Empirical evidence ahead. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 61, 134–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbtep.2018.07.002

Bellet, B.W., Jones, P.J., Meyersburg, C.A., Brenneman, M.M., Morehead, K.E., & McNally R.J. (2020). Trigger warnings and resilience in college students: A preregistered replication and extension. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 26(4):717-723. doi: 10.1037/xap0000270. Epub 2020 Apr 13. PMID: 32281813.

Sanson, M., Strange, D., & Garry, M. (2019). Trigger Warnings Are Trivially Helpful at Reducing Negative Affect, Intrusive Thoughts, and Avoidance. Clinical Psychological Science, 7(4), 778-793. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167702619827018

Boysen, G.A., Isaacs, R.A., Tretter, L., & Markowski, S. (2021). Trigger warning efficacy: The impact of warnings on affect, attitudes, and learning. Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in Psychology, 7(1), 39–52. https://doi.org/10.1037/stl0000150

Bruce, M.J., Stasik-O’Brien, S.M. & Hoffmann, H. (2023). Students’ psychophysiological reactivity to trigger warnings. Current Psychology, 42, 5470–5479. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-01895-1

Jones, P. J., Bellet, B. W., & McNally, R. J. (2020). Helping or Harming? The Effect of Trigger Warnings on Individuals With Trauma Histories. Clinical Psychological Science, 8(5), 905-917. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167702620921341

Bridgland, V.M.E., Jones, P.J., & Bellet, B.W. (2023). A Meta-Analysis of the Efficacy of Trigger Warnings, Content Warnings, and Content Notes. Clinical Psychological Science, 0(0). https://doi.org/10.1177/21677026231186625

Excellent work Kari.