The Cyclone Logs: Part 4

Shrödinger’s Floodhouse, The Waiting Game, and Community Spirit

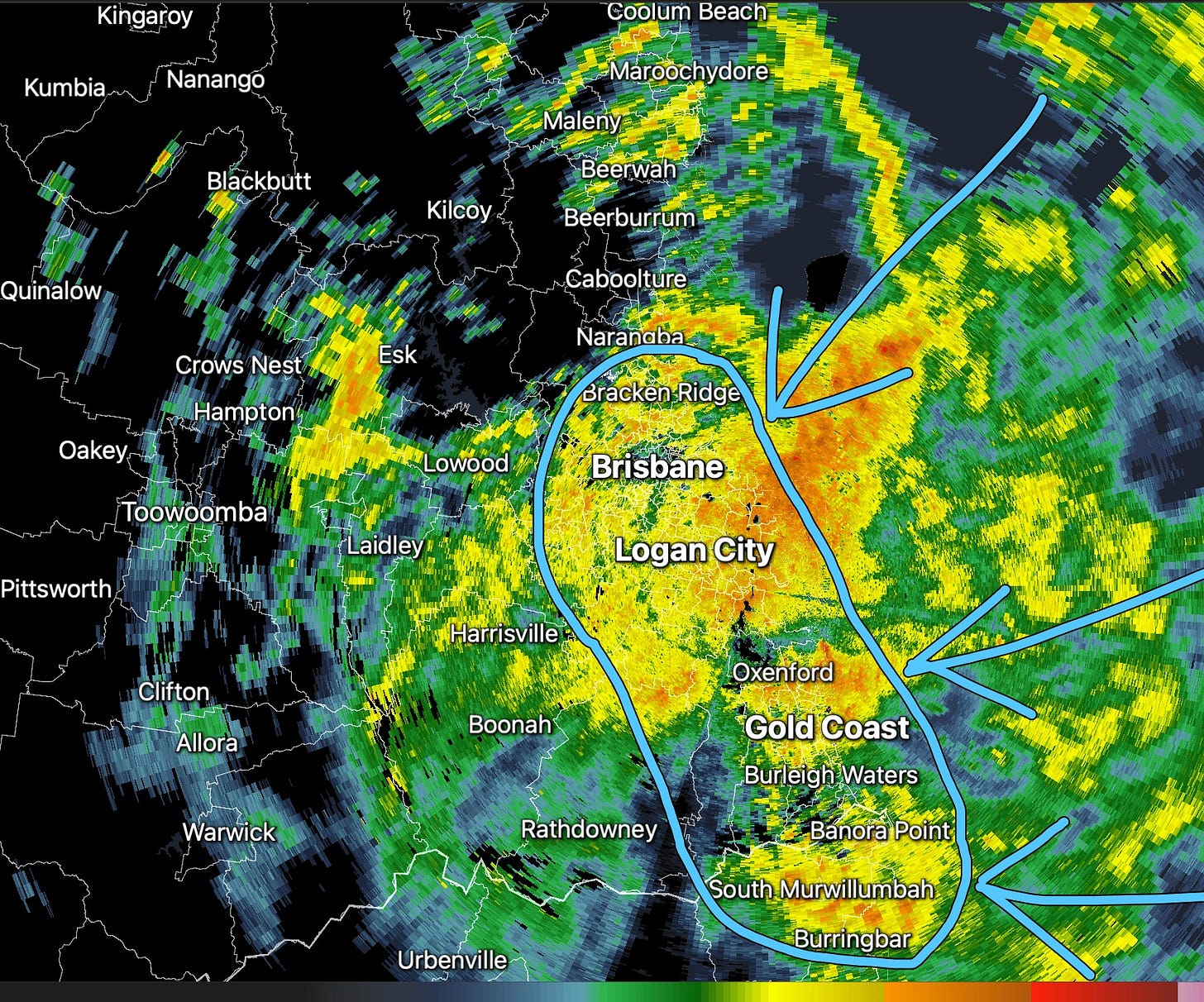

Alf finally made landfall as a tropical low last night, around 9pm, just north of Brisbane city.

And we felt it. The wind whipped up and the rain started lashing. It felt more hectic than Friday night, when Alf was still officially a cyclone.

There’s widespread reports of folks losing their roofs in the northern suburbs of Brisbane.

Trees down, power lines down, the number of homes without power continues to climb.

Public transport was briefly restored round my way, and then suspended again as conditions deteriorated. We’re expecting widespread flooding. Some areas of the city are already seeing inundation, and some rescues have been carried out as people attempt to drive through floodwaters.

At my place we are blessed. We still have power and internet. But water is starting to trickle down the walls. On the inside. It’s probably just condensation. Let’s just say we’re not well ventilated at the moment, and the air is, well, humid.

It could also just be gutter overflow seeping into the walls. There’s no way our gutters could keep up with the current volume of rain.

Or it could be roof damage. Let’s hope it’s not that. We’ll find out pretty quick if it is.

Things are pretty grotty out there and I’m going stir-crazy. I’ve been stuffing myself with cake and wine, and this is poorly balanced against a near-total lack of exercise. I haven’t run for the last three days and am starting to feel like a grumpy rain frog. And I’ve drunk more in the last three days than I have all year. I’m probably pickled.

I’m not good at staying indoors all day. I get cabin fever. So, I went out for a little nosey around the neighbourhood. So far, nothing to write home about. The water’s ankle-deep in some places, and the puddles are merging into ponds in the park. I suppose they’ll be lakes before long. I didn’t brave the park on foot; it’ll be kayak terrain tomorrow.

Here’s to hoping for the best, but preparing for the worst.

Back at home, I reflect on what it’s like to abandon a home at risk of flooding…

Uncertainty is Hard: Go Easy on Yourself

Once you’ve left your flood-threatened home, you really don’t know how it’s going to go. You can’t see it. Your house is Shrödinger’s house: at once completely fine (or at least, only as bad as you left it) and utterly destroyed. Until you’re able to get back and see it for yourself.

The human mind can perform many oscillations per hour, running through the scenarios and their associated feels:

“I’ve been overly cautious, and I’ll look silly for having panicked.”

“I should have seen this coming and packed more stuff up.”

“I was stupid for not moving that one thing to some other place. It’ll be destroyed.”

“I should have got insurance. I’m an idiot for not having insurance.”

You can’t know how it’s going to go. You can only keep your finger on the pulse, and play the waiting game.

In 2022, when I was playing the waiting game, my mate who sheltered me and the kitties helped me through it by keeping me informed, entertained, and distracted.

My mind kept drifting back to the unknown scenario playing out. That’s normal. To be expected. And he kindly, gently, brought me back to my present location: his couch, from where we checked in on Higgins Storm Chasing updates for the facts, and watched Garth Marenghi’s Darkplace for entertainment and distraction. And he fed me beer and Indian takeaway to keep my heart warmed and my soul nourished.

That’s about all that was possible, to be honest. I don’t recommend expecting much of yourself while playing the waiting game.

Try to stay informed. Don’t obsess over the unfolding situation. Just check in a few times for updates that will inform you of what you need to know that directly affects you – i.e., What’s the forecast? What roads are being closed/opened?

This is no time to be leaning into how awful things are for others if doing so dampens your spirits.

Take back as much control as you can by setting yourself a routine of sorts and making yourself comfortable where you are. And make lots of small decisions if you have the bandwidth. Like, what are we going to watch on TV? What comforting meals are we going to eat? Really. Keep it that simple.

A lot of folks struggle to eat when they’re anxious. Try a little anyway. It helps kick the parasympathetic nervous system into action, calming you as well as keeping you well nourished and fuelled for the hard yards ahead.

If you don’t have the bandwidth for decision-making, abdicate that to your host. And tell them that.

You won’t be making any big decisions until you’re able to get back to your house to inspect. You’ll know when that is. It’ll be when the rain has eased up enough for the floodwaters to recede; when the roads are open and you can physically get there.

If you’re supporting someone else through the waiting game, be prepared to babysit a little. Folks need soothing and distracting when their life or livelihood is up in the air.

If you’re not hosting flood evacuees, check in relatively regularly via text to see how they’re doing. Non-response isn’t anything to worry about; they might be fielding lots of check-ins. But it’s important to reach out and let people know you care, and that you’re there should they need a shoulder now, or some practical support later on. Something as simple as sending funny memes helps remind people you’re thinking of them, and can lighten the damp mood a little.

If you’re hosting, light entertainment to keep overactive minds distracted is ideal: movies, TV shows, card games, board games, and idle gossip are just grand.

And be prepared to make decisions on their behalf if they’re too preoccupied to make their own decisions. Setting structure and routine in place will help, and offering suggestions for activities and meals will add structure and clarity that will help when all sense of normal has gone out the window.

Working Through the Aftermath

After the worst is over, you’ll want to check out your Shrödinger House.

You might not be able to get there right away, so prepare for the possibility that your waiting game gets painfully prolonged.

In 2022, I couldn’t get near my house for the first 24 hours after the rain had stopped. The roads weren’t passable, and I couldn’t even see the house at ground level from the distance I was able to get to. I managed to get up onto some scaffolding of a construction site up the road, on the opposite side, and pointed out my house to the builders. Versed in measurements as they are, they estimated the water was about 10mm from the windowsill at that point.

The next day I was able to wade across the road, through communal shitwater, to see the property. The backyard was so flooded you still couldn’t see the top of the fence. I couldn’t open the front door as it had seized shut. It took another couple of days to get a locksmith out to force it for us.

By then, the receding floodwater had revealed a wheelbarrow perched atop my fence. The highlight of what was quite a surreal week. It wasn’t even my neighbour’s wheelbarrow. It stayed there all week.

Once inside, we were then able to survey the damage. We were prepared for the extent of it by then, as we’d seen the high-water line all around the house. It was obvious everything below the windowsill had been submerged.

Losing stuff like furniture isn’t that awful. Losing sentimental stuff can be. But everyone’s experience of loss is different, and you might be impacted by losses in ways you weren’t expecting. Or you might find yourself surprisingly unaffected. You won’t really know until it’s time.

If you own the house, you’ll have to grapple with the insurance issue. And where you’ll stay while you get things fixed up. I don’t envy anyone that task. You’ll need to prepare to possibly rent somewhere in the interim, or stay with family or friends for a little while. You’ll need to work out a plan that will work for your unique circumstances.

If you don’t own your house, you’re in a different situation. It can be better, really.

If the place it still liveable, you can expect to pay reduced rent or no rent at all (depending on the level of damage) while things are being fixed. You’re not responsible for the cleanup. And your property manager has to keep you informed of what to expect and how long it will take, and offer you an out if you prefer.

If the place isn’t liveable, you can expect to stop paying rent from the date you evacuated, regardless how long it takes you to shift your flood-destroyed belongings (and you should be able to get help with that from council or the Mud Army). Again, you’re not responsible for the cleanup; only the removal of your stuff. And you’ll get your bond back quickly.

If your real estate or landlord are c*nts about it, I’m sorry. Mine were. Their first priority was that I photograph the house for insurance purposes. They didn’t check in on whether we were ok, or whether there was anything we needed. Upon receipt of the photos indicating the extent of damage, they declared the house unliveable and issued us with forms to that effect. And they continued to charge us rent until all our stuff was gone, insisting the owners couldn’t come and inspect until after. Which was absurd considering it was just a disaster zone we weren’t living in at that point.

We had to fight for our bond back, and reimbursement for the locksmith, which I’d had to organize myself. And we dropped the fight for our overpaid rent. It wasn’t worth pursuing.

We’d asked the council for help shifting some of the heavier, damaged stuff. They kept promising and not delivering. And the Mud Army never showed up round our way.

This all added insult to injury while we were ‘between homes’, and it needn’t have been that way. But that’s how it was, and we coped because we understand the world isn’t inherently fair and we can only do what’s within our control.

One foot in front of the other, each day as it comes, and everything gets done.

Our friends were amazing. They came out in waves to help with the dirty work of clearing out what was destroyed and salvaging what could be salvaged. And local school PTA and church groups came round with snacks, bottled water, gloves, masks, and hand sanitiser to help us through with a smile.

Finding a new place to live sucks, especially in the current rental market. So, figure out what’s the best interim option for you: does a friend or family member have a spare room for a few weeks? Or a couch you can surf on? Or would you rather suck up the cost of an Air BnB to have your own space?

For me, it was couchsurfing for just under four weeks, with three kitties. That was my option, thanks to a friend (with a larger couch) who happens to love cats and had plenty of space for us. They essentially just let us have the lounge, relatively undisturbed, for that time, which was really generous. I still went stir-crazy and barely slept the whole time. But having a secure base to house-hunt from was a real help.

It’s important to manage expectations for what else can get done during this time. I was doing my PhD, it was teaching season, and I was supporting a family member through a crisis. I was able to pause most work on my PhD, as it wasn’t a critical time and I could catch up. That meant I was able to show up for my students and still support my family while making finding a home my top priority.

You’ll need to find a way to dial down other commitments that don’t need your full attention so you can stay on top of the ones that do while you’re ‘between homes’. Go easy on yourself; now is not the time to try to be everything to everyone.

While it’s a rough experience to go through, counting the relative blessings does help keep things in perspective. Yes, I’d lost my home and most of my stuff. Yes, the real estate and owners were c*nts about it. Yes, the council were useless. But I had a dry roof over my head. I had wonderful friends who helped out in all ways imaginable. And total strangers helped for no reason other than that most people are good. They really are. And disasters bring out the best in most of us.

Strong Communities are the Bedrock of Survival

Whether you’re directly impacted or not, you’ll probably want to get out and survey the damage in your local area as soon as possible.

Journalists may approach people sensitively to ask for their participation in a story. If a journalist approaches you for your own story, you can decline if you’re not keen. They might press you a little, or they might not. Reiterate that you don’t want to share your story if they do press you. They cannot report on you, or photograph or film you or your home, without your consent.

If you decide you want to share your story, that might be helpful for you and others. I shared mine with an ABC journalist when I wasn’t able to get to my Schrödinger house. It felt right. It felt useful. I didn’t feel pressured, and the journalist was kind and sensitive.

If you are not a journalist, and this is not your job, please do not photograph people’s homes without their consent. They’re doing it tough enough without you invading their privacy and violating their autonomy.

The appropriate thing to do would be to approach the person and ask them if they’re ok, if they need anything, if there’s anything you could do to help. Ideally do this as part of an official volunteer group that’s gone out prepared with bottled water, food, and cleaning supplies and services. It’s no good asking people if they need anything if you’re not actually prepared to help them. You’re just in the way, making a nuisance of yourself.

If it feels a bit off to you to ask someone for their consent to photograph the wreckage that was their home, that’s probably your moral compass talking. Telling you not to invade their privacy to satisfy your own curiosity. Telling you that the right thing to do would actually be to just leave them the fuck alone.

For me, the worst part of the 2022 floods that added insult to the injury of losing my home and the shitty response of the real estate and owners was actually randos stopping by every few minutes to take photos of my house.

Many of them seemed either oblivious to the fact that I was standing out the front, glaring at them. Or they didn’t care. They just wanted their shot for the ‘gram, probably captioned with a virtue signal about their own achey-breakey heart.

Not one of those people asked me if I was ok, if I needed anything, if there was anything they could do to help. Not one asked for my consent before photographing the wreckage of my life. Including with me in the frame.

That’s the one thing that still sticks in my throat three years later, after I’ve all but forgotten the rest.

Please, be better that that.

Don’t plaster other people’s tragedies over social media as a signal of your own virtue.

If you genuinely want to help, get out there, get your hands dirty, and don’t crow about what a hero you are. Just do the work and be satisfied with knowing that you brightened someone’s darker days. Like the lovely PTA and church ladies who brought us sandwiches and cake in 2022 and put the smiles back on our faces.

Be the anchor of calm and hope in someone else’s storm. Help restore the faith that may have been damaged by more formal systems and processes.

Strong communities can survive almost anything, and they’re made up of people like us.