Get in the Zone of Optimal Stress

What doesn't kill you may well make you harder to kill.

I read a pop-psych article the other day (yes, I occasionally read pop-psych; sue me) about how ADHD isn’t static in terms of symptom severity. And some people literally overcome it to the point that they no longer have symptoms. Not just kids growing out of it, but adults actually getting on top of it, some of them sans meds.

The science cited in the pop-psych piece is published in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, a top-tier journal. And yes, I read the actual paper just to be sure the pop-psych hadn’t exaggerated or misrepresented its findings.

The TL:DR is this: ADHD may turn out to be a relapsing-remitting condition, meaning that there are conditions under which symptoms are worse, and conditions under which they go away entirely. Over a loooong-term longitudinal study with nine assessments over 16 years, remission periods in those with fluctuating ADHD (that’s not all, but the majority of those with the condition) were associated with higher environmental demands.

In short, most folks with ADHD do better when life is more demanding, and their responsibility load is higher.

While many folks may well be surprised by this, I am not.

Why am I not surprised?

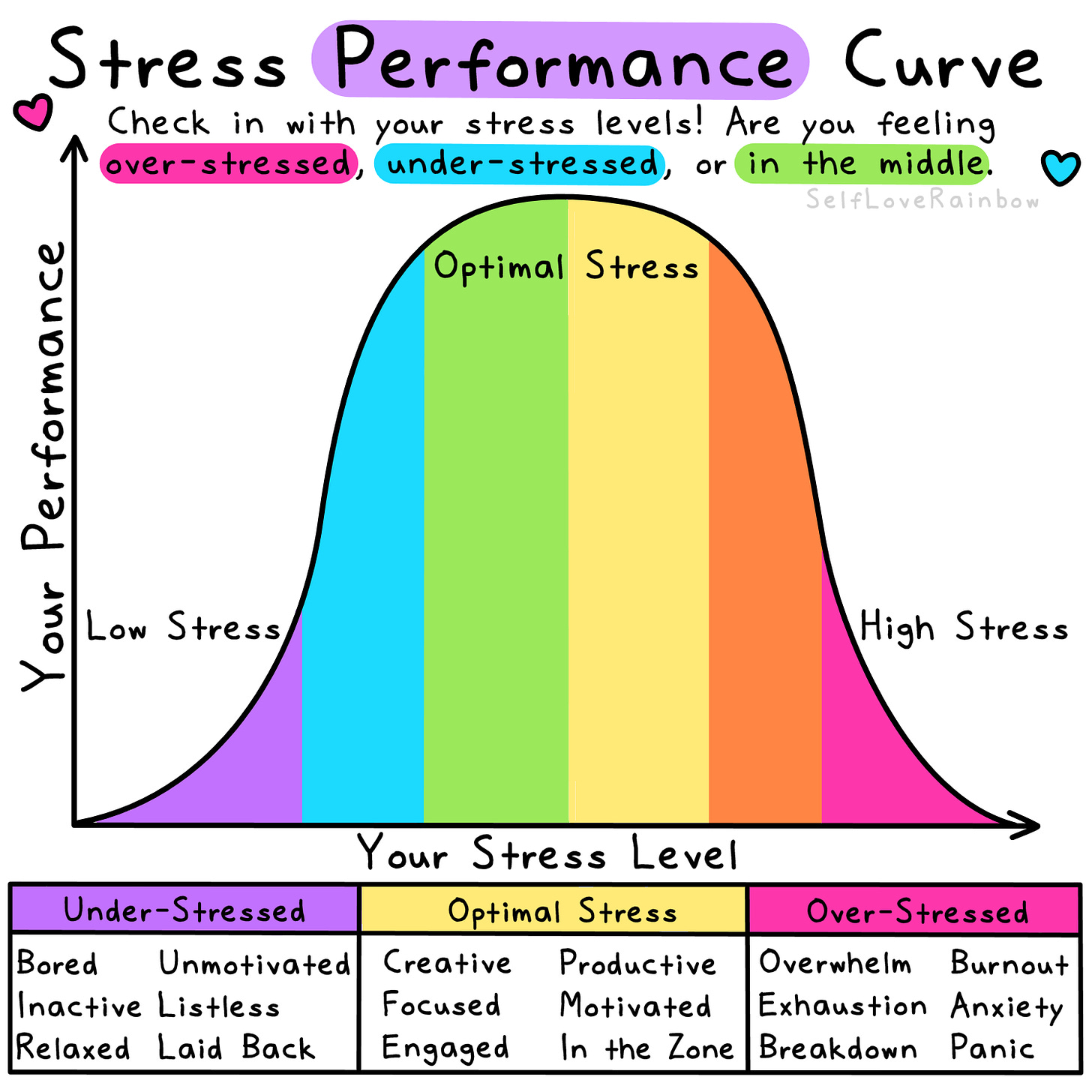

Well, because eustress, the zone of optimal stress in which an individual is both challenged and rewarded because they are confident in their ability to cope.

A lot of the time, folks with ADHD spin their wheels because they’re either under-stimulated or overstimulated – i.e., not in that optimal zone. Folks with ADHD are often temperamentally well cut-out for highly stimulating work environments that require complex problem-solving under pressure. Think paramedics, firefighters, and chefs. Think athletes, musicians, and comedians.

Our modern work environments often tend to be quite under-stimulating, particularly if you work in an office, sat at a desk, responding to predictable, likely monotonous, demands. So, many of us seek high-carb stimulation through social media scrolling or checking the news on repeat. Some of us pick fights with loved ones. Or bosses. This might tip the balance to overstimulation.

That goes for people without ADHD as well as with.

Which brings me to my shower thought of the day, the main point of this piece. Regardless whether you think ADHD is currently over-diagnosed (I do), and regardless whether you think it often serves as a convenient excuse for underperforming or flaking entirely (I do), I think the issue highlighted in this paper is almost universally applicable: a lot of us are operating outside the zone of optimal stress most of the time. And that leads us to underperform.

Meanwhile, most highly successful people have one thing in common: they grind really hard in the zone of optimal stress, and that leads them to outperform others.

Life hack for the doubters: If you ever doubt your ability to cope, or lack the confidence to try, just give whatever it is a whirl and see. You might not manage whatever it is in its entirety, but I’d be surprised if you achieved nothing at all. Whatever you do manage to do sets the bar at its new lowest point. You can now engage in future activities with confidence that you know what you’re definitely capable of, and then you can stretch yourself a bit further.

So, regardless whether you have ADHD or not, you should be aiming to live as much of your life as possible in the zone of optimal stress. Not someone else’s zone of optimal stress. We don’t all have the temperament to be a paramedic or a rockstar. It has to be your own zone of optimal stress.

I’ve often lamented the fact that I have the temperament and gut strength to be a paramedic, and yet I took a different path. A winding path that has left me chronically under-stimulated, underwhelmed, and ultimately, underachieving. Not saying I’m going to retrain as a paramedic. That doesn’t actually appeal to me. Just that I need to figure out how to channel this temperament into the right tasks, workload, and workflow to put me in my own bespoke zone of optimal stress.

This is, perhaps counterintuitively, the zone I found myself in for the home stretch of my PhD. That time when I should have been overwhelmed and highly stressed. While I generally felt under-stimulated for most of the journey (not because it’s not hard enough; believe me, it was plenty hard enough), it was only really when I stared down the barrel of potentially harsh examiner feedback with a gun-to-head deadline that I did my best work. Not only did I manage to crank out large volumes of work in my zone of optimal stress, but I found my thinking was at it clearest. The clearest it’s ever been. And I learned quickly, made rapid improvements, and felt much more satisfied with my outputs.

And, get this: under the intense pressure, because it was in the sweet spot, I was pretty darned happy. Not that I didn’t have my cranky moments. Sleep-deprivation came into play for the final fast finish segment of the journey. But, for the most part, my planning skills were on fire, my problem-solving skills levelled up, and my productivity almost impressed me.

And now? Well, lots of reps of a hefty load builds muscle. So now, pretty much everything else I do is easy by comparison, and I have no fucking excuses anymore.

What did I learn from this? I need pressure not just to thrive, but to cope. You might need less pressure, or maybe more. Up to you to figure out the right dose for you. The important thing is to figure out what that dose is, and structure your life around it.

What I’ve figured out is that, if I put a bit more pressure on myself than a 21st century lifestyle typically does, I’m healthier, happier, and more productive. So, one of my main goals for 2025 is to figure out how to get into my zone of optimal stress on a daily basis so I can give myself the life I want, and leave nothing on the table for deathbed regrets.

Time to shift gear and get out of the comfort zone.