Big-T Trauma: PTSD

How to recognise and respond compassionately to posttraumatic stress disorder

This is Part 1 of a four-part series on the major trauma- and stressor-related disorders.

This week’s post is a longread on PTSD, how to recognise it, and how to respond to it compassionately. Grab a cuppa, put your feet up, and settle in…

I’d like to issue a cease-and-desist notice for the abuse of the word trauma. The word has become chronically misused to the point of losing meaning. And it’s important the word retains its meaning because understanding trauma is crucial for the development of a trauma-informed society. And when trauma gets conflated with things that are merely stressful, challenging, or unpleasant, then we stray further from that goal. Delineating the distinction is an important step in attaining clarity, and with clarity we can be responsive to the needs of survivors.

One key factor sets trauma- and stressor-related disorders apart from other psychiatric diagnoses: they are traceable to a specific event or series of events. For this reason, I prefer to conceptualise trauma less as mental illness and more as psychological injury. An injury is incurred through an adverse event, and injuries can vary in severity, with some taking longer to heal from than others. And, as with a lot of physical injuries, healing from psychological injury is not a pain-free process; it’s an immense test of strength and courage. And those who pass the test tend to grow from their experience. Of the wisest people I know, all are trauma survivors.

PTSD is the most well-known of the trauma- and stressor-related disorders. And to be clear, it is a disorder, not a ‘normal’ reaction to a traumatic event. I’ll explain why, with a walk-through of the core symptoms that distinguish PTSD from other responses to traumatic or stressful experiences. If you’re able to recognise PTSD when you see it, you’ll be better equipped to respond to it with trauma-literate compassion.

It all hinges on an event

The #1 criterion for a diagnosis of PTSD is the traumatic event itself. And, at risk of sounding a bit dogmatic, it’s not your subjective appraisal of the event that makes it traumatic. A potentially traumatic event is an objectively extreme experience that would cause most people to feel terrified or overwhelmed or both. To be considered potentially traumatic, an event must involve exposure to actual or threatened death, serious injury, or sexual violence.

In the majority of cases, the event is either directly experienced, or witnessed in person. In a smaller proportion of cases, an individual can be traumatised by learning of a traumatic event happening to a close family member or friend. I’ve worked with such cases when counselling families of murder victims and survivors of suicide, and the anguish the news brings is palpable, felt physically. In cases involving actual or threatened death of a loved one, the event must have been either violent or accidental. Learning of a loved one dying of a terminal illness, while undoubtedly distressing, is not considered a traumatic event.

You’ve probably heard of vicarious trauma, and yes, it’s a real thing. But the criteria are pretty strict and tend to apply predominantly to first responders and other frontline professionals whose role requires them to be exposed to aversive details of traumatic events – either repeatedly, or to an extreme extent. Examples include exposure to details of child abuse in the case of police officers, healthcare professionals, or child protective services. Or exposure to stories of persecution and torture in the case of human rights workers. The diagnostic criteria do not assign trauma status to you if you have voluntarily exposed yourself to distressing material through the internet, TV, movies, or pictures, unless the exposure is specifically work-related and therefore unavoidable by any means other than quitting your job.

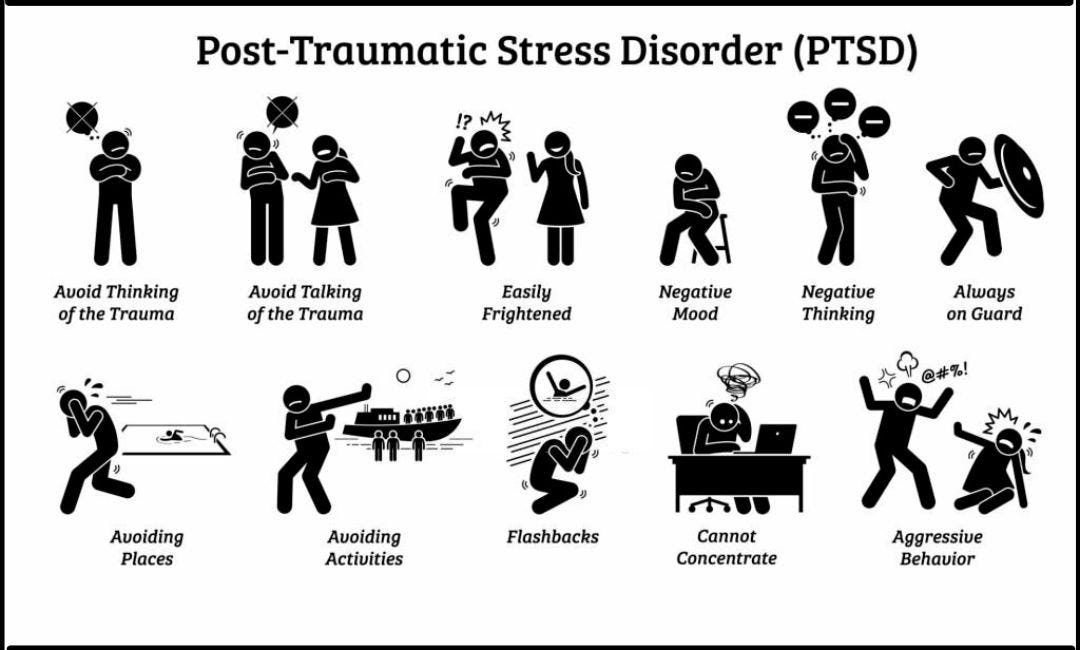

When we’re clear on the types of events that can lead to PTSD, then we are better able to observe an individual’s recovery trajectory in the days, weeks, and months after the event has occurred, ready to respond to support needs as they arise. There are four key symptom clusters we need to look out for in assessing how well recovery is going: intrusions, avoidance, changed cognition and mood, and hyperarousal. Let’s take a stroll through those.

Intrusion alert

The second key criterion for PTSD is that the individual experiences one or more intrusion symptoms associated with the event. Intrusions may manifest in five different ways:

Recurring intrusive and distressing memories of the traumatic event occur involuntarily, regardless of time and setting. This means the individual cannot make them stop by sheer force of will, and functioning may be disrupted by their unbidden appearance.

Recurring dreams occur in which the content or emotional timbre of the dream is related to the traumatic event. Such dreams tend to be highly distressing and can lead to pervasive issues with sleep. People suffering from recurring traumatic dreams may fear going to sleep because they are unable to control the content of their dreams, and it’s not uncommon for people to use alcohol as a means of coping to dull down the likelihood and intensity of traumatic dreams.

Dissociative reactions, often referred to colloquially as flashbacks, involve the individual feeling or acting as though the traumatic event were recurring in real time. There’s a continuum of severity with dissociative reactions, with the lower end of the spectrum aware of the distortion while the more extreme end of the spectrum involves a complete loss of contact with the present context.

Intense or prolonged distress occurs when the individual is exposed to either internal or external cues that serve as reminders of the traumatic event. These are what’s colloquially known as triggers. External cues are sensory, so visual similarities, and reminiscent smells or sounds for the most part. And internal cues involve a cascade of thoughts, feelings, memories, or bodily sensations associated with the traumatic event.

An individual may also have intense physiological reactions to internal or external cues that serve as reminders of the traumatic event. So, when reminded of the event, an individual might feel their heart pounding, their hands sweating, or their body trembling. These sensations can be very overwhelming and lead the individual to feel they cannot cope.

All people who have PTSD have at least one of these symptoms. Without intrusions, the individual does not have PTSD. Before I understood PTSD, and back when I actually had it myself in my twenties (before I trained as a therapist), I was unaware of the range of forms intrusions could take. So, I didn’t realise my intrusive thoughts and memories, and my recurring dreams, were actually symptoms of PTSD. And because I didn’t connect the dots, I didn’t get the help I needed until I’d already got myself a secondary problem thanks to my attempts to avoid the pain of having to relive my trauma in various formats. That brings us to avoidance.

You can’t hide from trauma

Avoidance goes hand in hand with intrusions, as it’s only natural an individual would want to avoid the distress of re-experiencing any aspect of their traumatic experience. But it doesn’t help. In fact, more than just a symptom of PTSD, persistent avoidance is a core maintaining factor that hinders recovery. It’s important to note that the avoidance must be persistent. There’s nothing wrong with avoiding difficult experiences from time to time; arguably that’s a healthy mechanism for regulating difficult emotions, particularly when you’re in a setting that’s not conducive to leaning in. But when avoidance is persistent, it limits functioning and wellbeing.

Avoidance can relate to either internal or external reminders of the traumatic event. Avoidance of internal reminders involves trying to push away or otherwise not engage with distressing memories, thoughts, or feelings either about or closely associated with the event. And avoidance of external reminders involves avoiding people, places, activities, situations, or even conversations that might trigger those same distressing memories, thoughts, or feelings.

No avoidance means no PTSD. That’s why engagement with the memory of the traumatic event is one of the key interventions therapists use with trauma clients. The longer we delay engaging with the memory, the more we risk entrenching avoidant coping strategies that can also cause secondary problems, if exacerbating the PTSD weren’t bad enough.

I’ll offer up a personal example: I still sometimes have distressing dreams relating to a particular traumatic experience in my past, though I no longer try to avoid the possibility of having such dreams. For many months after the experience, I struggled to sleep due to distressing physiological responses to unavoidable environmental triggers. I also became afraid of sleeping because, when I was finally able to fall asleep, I would relive the event in my dreams. I ended up with a drinking problem because of my attempts to dampen down my responses to triggers, soothe my jangly nerves, and lull myself into a dreamless sleep where I wouldn’t be confronted with my fears. I’m proud to say I overcame that, and now have a healthy relationship with alcohol as well as pretty good sleep most nights. And while my dreams are still sometimes rudely interrupted by that same dream again, it’s rare, perhaps just a couple of times a year. Nothing that can’t be easily managed by self-soothing upon waking, and later unpacking with my best friend if I feel the need to.

When someone is avoiding, it’s all too easy to become an enabler, helping the individual to avoid distress. It’s understandable that we don’t want our loved ones to experience distress any more than they do. But when we help people avoid reminders of their trauma, we are, inadvertently, exacerbating it and delaying recovery. The ironic outcome of our efforts at care is a padded cell for the individual to live in, buffered from distress only if their freedom to live life is curtailed. That’s not a worthy trade.

The dark side

A less well-known but key feature of PTSD involves negative changes in thought patterns and mood after the event, either a worsening of pre-existing negativity, or a new development in a previously upbeat and optimistic person. There are seven different ways in which negative cognition and mood can manifest, and an individual must demonstrate at least two of these for a PTSD diagnosis:

A trauma survivor might be unable to remember important aspects of the traumatic event. This is typically due to dissociative amnesia – i.e., gaps in memory that you wouldn’t expect. You might expect memory gaps in an individual with a head injury, or under the influence of alcohol or other drugs, but dissociative amnesia leads to memory gaps in the story of the traumatic event in people who are able to recount non-trauma memories without difficulty.

A survivor may also develop persistent and exaggerated negative beliefs or expectations about themselves, other people, or the world. This might manifest as feeling like they are broken, or that others can’t be trusted, or that the world is a dangerous place.

Survivors may also have persistent, distorted beliefs about the cause or consequences of the event. This leads the individual to unfairly blame themselves for the traumatic event or its consequences, or to blame others who were not realistically responsible.

Trauma survivors may also experience a persistent negative emotional state, be it fear, horror, anger, guilt, or shame. Because there is a range of possible emotions, it’s important to be mindful that the emotional state of trauma survivors is quite diverse, so it may not be obvious that trauma is the cause.

Survivors often demonstrate diminished interest in participating in meaningful activities, including activities that previously brought them great joy.

A survivor may also feel detached or estranged from others after the event. This would be difficult to gauge in someone who was already detached or estranged, but should be quite obvious in someone who was previously very socially engaged and related easily to others.

And, as with individuals experiencing depression, a trauma survivor may also struggle with a persistent inability to experience positive emotions. This means they feel unable to experience happiness, satisfaction, or loving feelings, a state known as anhedonia.

I’ll self-disclose again, in the interest of bringing this point home. During my own experience of PTSD, I practically shut myself away from social contact and didn’t believe I could possibly be understood, so I didn’t tell anyone what I was going through. I wallowed in self-pity and regret. If it weren’t for work, I might have not engaged with the world at all. But I didn’t have a choice, as I had no financial safety net. The end of one’s tether can be quite slippery, and I was at least cognisant of the need to hold on. But I quit going to the gym and gained weight as a result. I didn’t cultivate any hobbies or passions outside of work. I developed a suspicious attitude toward authority figures, always waiting for the other shoe to drop. And I said no to most invitations to go out and have fun. But I was lucky. I had caring friends who kept reaching out. They understood that a no nine times out of ten did not mean I didn’t love or appreciate them, just that they’d need to persistently show love and care for me without expectation that I would reciprocate. And thanks to their love and care, I was able to reintegrate into social life gradually, affirmed that I could take my time and they would still be there.

Locked and loaded

The last of the key criteria for PTSD is a state of heightened physiological arousal and reactivity associated with the traumatic event. As with the other criteria, this must be something that either began or worsened after the event, not a continuation of pre-existing anxiety. Heightened arousal and reactivity can manifest in six different ways, and an individual must demonstrate at least two of these for a diagnosis of PTSD:

Irritability and angry outbursts with little or no provocation. Being irritable can easily fly under the radar, but it’s important to take note if it’s ongoing, as it’s an indicator that the individual has become more reactive to stimuli. Outbursts may occur that are disproportionate to any stimulus, and are typically expressed as either verbal or physical aggression toward other people or objects. While aggression toward others or the destruction of property are not acceptable behaviours, it’s important to be mindful of their genesis, and respond accordingly.

Reckless or self-destructive behaviour. It’s not uncommon for trauma survivors to engage in behaviours that are likely to bring them harm, as though they either believe they are invincible or simply don’t care for their own wellbeing. Such behaviours might include risky substance use, drunk or otherwise dangerous driving, risky sexual encounters, or high-octane thrill-seeking behaviour.

Hypervigilance. A trauma survivor may find themselves perpetually on guard, watching and waiting for something to happen. The sound of a pin dropping can be heard by a trauma survivor who is primed for fight or flight.

Exaggerated startle response. Primed as they are for fight or flight, trauma survivors may seem jumpy, reacting to every unexpected sound or movement in their environment.

Problems with concentration. Hypervigilance causes the trauma survivor’s attention to be scattered in multiple directions in an attempt to ward off danger. This leads to difficulties focusing or concentrating on any task that’s not immediate survival-related.

Sleep disturbance. As with pretty much all other mental health issues, the psychological injury of trauma brings with it challenges with either falling asleep or staying asleep, or restless sleep that fails to refresh.

Be gentle with folks who are experiencing heightened arousal or reactivity. It’s exhausting being on guard all the time, as I can attest to. In my final self-disclosure, I feel some shame in admitting to most of these symptoms. My sleep was wrecked, as I’ve mentioned, and the quiet of the night was the worst time for hypervigilance. Every little creak of a door or gust of wind spelled danger, and I was primed ready to face it. I was at times quite reckless with my health and safety, on the occasions I found it within me to leave the safety of my home. I think it was largely because I was so emotionally numbed out that I didn’t really register that I could hurt myself, and I didn’t care as much as I would have if I weren’t already hurting so much. I became prone to picking fights, not with loved ones, but with a system I thought was unjust. I rationalised it as righteous, but in truth it was a punching bag, and I was a wrecking ball. I did things I later regretted, and I hurt people who didn’t deserve it. The old cliché is true: hurt people hurt people.

Bonus symptom: dissociation

Some people experience dissociative symptoms along with the rest. These are bonus symptoms, bestowed on the unlucky few, not the majority. Dissociative symptoms can involve either depersonalization or derealization or both. Depersonalization is a persistent or recurrent experience of feeling detached from one’s own mental processes or body such that one feels like an outside observer or as though one were in a dream. The experience has a sense of unreality of self or body, or of time moving particularly slowly. And derealization is a persistent or recurrent experience of unreality of one’s surroundings such that the world is experienced as unreal, dreamlike, distant, or distorted. It’s important to note that, while less common, these are still symptoms of PTSD, and not to be confused with possible psychosis.

The trajectory after trauma

I self-disclose because I want to normalise the experience of PTSD. But I also want to be clear that PTSD is not the standard response to a traumatic experience, and therefore it’s not one we should expect. It’s absolutely normal to have a large number of the symptoms I’ve described after a traumatic event, and that tends to taper off in the days and weeks after. It’s only if these symptoms have been present for at least a month that a diagnosis of PTSD is considered, as this is a prolonged response that is not returning to baseline without intervention. For the most part, we can expect that even if a traumatic experience has hit us hard, we will return to baseline within a few weeks, without psychotherapeutic intervention, and ideally with the support of loved ones.

Delayed expression of PTSD is rare, but does occur, with a small proportion of trauma survivors not manifesting the full range of symptoms until at least six months after the event. This doesn’t mean folks should be worried about PTSD coming on out of the blue down the track, though. That doesn’t happen. It’s far more likely that some symptoms are present from the outset, but the full criteria for a PTSD diagnosis aren’t met until later. Generally speaking, if symptoms are reducing after the first few days or weeks, you’re on a trajectory toward recovery and should only expect things to get better, not worse.

What do we do with this knowledge?

Firstly, don’t go trying to diagnose yourself or anyone else. If something potentially traumatic has happened in your life and some of these symptoms are striking a chord with you, then make an appointment with a therapist who specialises in PTSD so you can have a full assessment. If someone you know is experiencing a range of these symptoms, you may, if you feel comfortable to do so, gently broach the topic with them and explore whether they would be open to getting a formal assessment if they have not already done so.

Beyond that, please be compassionate. Interpret what you are observing as indicators of the intense pain of psychological injury. Endeavour to understand and support, and do not either infantilise the survivor or enable avoidant coping. That’s just as important if the survivor is you.